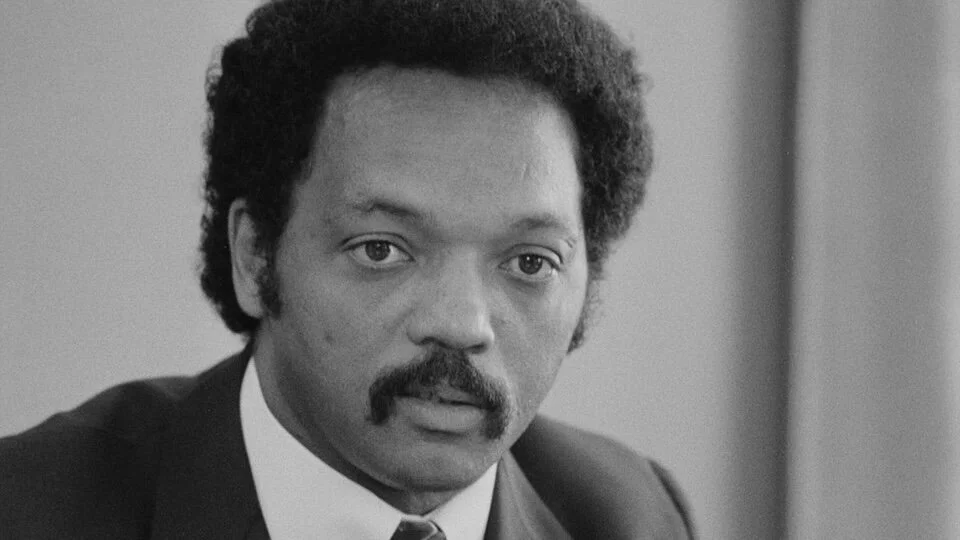

On Jesse Jackson, Asian Americans, and the PC(USA)

Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

The murder of Vincent Chin in 1982 remains one of the most painful chapters in American history. It was a moment where the promise of the American dream was shattered by a baseball bat and a climate of hate.

In the wake of that tragedy, the Asian American community found an unexpected but vital ally in the Baptist preacher from Chicago and founder of Rainbow/PUSH, the Rev. Jesse Jackson.

As an Asian American looking back at this history, I see Jackson’s presence at the rallies for Chin as a definitive punctuation mark on his life’s work. It was the moment his advocacy for the marginalized truly embraced the idea that all means all.

This intersection of history is particularly important on Feb. 19. This date carries the heavy weight of two very different legacies. In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066.

This order led to the forced relocation and incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans in concentration camps. It was a day that defined Asian Americans as perpetual foreigners, regardless of their citizenship or their love for this country. It was a time when the government decided that the color of a person's face was enough to take away their freedom.

Exactly 34 years later, on Feb. 19, 1976, President Gerald Ford signed a proclamation that officially ended that dark chapter. In Proclamation 4417, Ford finally admitted the national mistake of the internment. He urged the American people to resolve that this kind of action shall never again be repeated.

This date serves as a bridge between a history of exclusion and a hope for belonging. It reminds us that while the state can cause great harm, it is also capable of admitting it was wrong.

When Jesse Jackson arrived in Detroit in 1983 to stand with the family of Vincent Chin, he was stepping into that same historical stream. The decline of the American auto industry had created a toxic environment.

Vincent Chin was targeted because he looked like the face of economic competition from Japan. When his killers were given probation and a small fine rather than prison time, it felt like 1942 all over again. It felt like the law did not see Asian American lives as worthy of protection. The judge in the case even said these were not the kind of men you send to jail, implying that the killers were more relatable than the victim.

Jackson recognized that the struggle for Asian American rights was tied to the broader struggle for justice in the United States. He stepped into a space where many Black leaders had not yet gone. He helped bridge a gap between communities that were often pitted against one another by the larger culture.

During his appearances, Jackson spoke with a moral clarity that validated the grief of the Asian American community. He famously stated that we are all in the same boat, and if there is a hole in the Asian end of the boat, the whole boat is going to sink.

For many Asian Americans, Jackson’s advocacy provided a sense of visibility that had long been denied. Many in our community are often viewed as the "model minority," a label used to silence our problems and separate us from other people of color. By standing with the Chin family, Jackson rejected that narrative.

He showed that the Rainbow Coalition was more than a slogan. It was a commitment to the idea that no one is free until everyone is free—even disadvantaged white people. He understood that if the rights of an Asian American man in Detroit could be ignored, then the rights of every person were in danger.

This era was also a time of deep reflection for our Church, the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). While the denomination was busy with its own historic reunion in 1983, it began to explicitly include Asian American concerns in its mission.

The Church started to move toward a "pan-Asian" understanding of justice, mirroring the movement Jackson supported. In the years following the Chin case, the PC(USA) began to address the "perpetual foreigner" myth and the scapegoating of Asian Americans. This work ensured that the voice of the Church was not just a white or Black binary, but a multiracial tapestry.

The sentiment shared by Jackson aligned with the developing theology of the PC(USA). The Church held that the Body of Christ suffers when any part of it is targeted by hate. The denomination began to issue robust updates on human rights that included the specific civil rights of Asian Americans.

This moved the Church away from a model of "missions" toward a model of mutual advocacy. It recognized that the struggle of the Japanese American families in 1942 was connected to the struggle of the Chin family in 1982.

Ultimately, Jesse Jackson’s involvement in the aftermath of Vincent Chin’s murder served as a pivot for the modern civil rights era. By showing up, Jackson proved that his vision of a just society was big enough to include those who did not share his specific heritage but shared his yearning for justice. It was a testament to a career defined by the belief that when we say all, we must mean every single one of us.

This belief reinforces the idea that the Sacraments and the Gospel are only fully realized when we stand up for those facing systemic violence.

On this anniversary of both the internment order and its ending, and in recognition of Jackson’s death, we remember that justice requires an active, multiracial choice to never let history repeat itself.