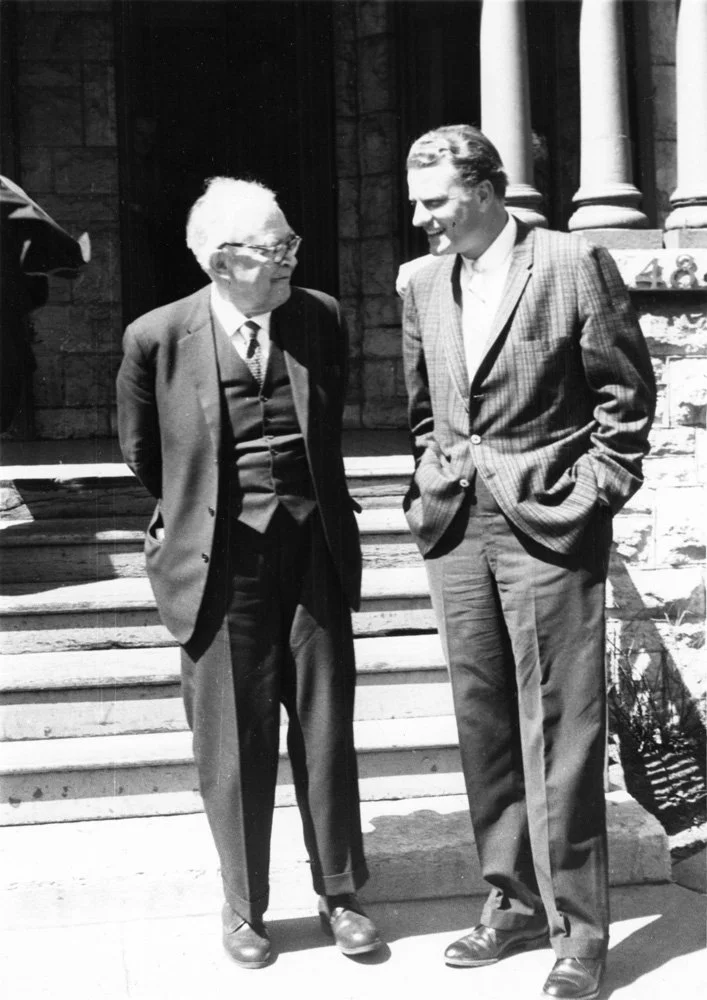

Reformed theologian Karl Barth vs. Billy Graham

Karl Barth and Billy Graham, April 16, 1962. Photo: Anne Barth. University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-09243, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

I have always been a bit of a Presbyterian theology nerd, and for someone like me, Karl Barth stands out as probably the foremost Reformed theologian of the modern era.

My thinking on Barth vs. Billy Graham was actually prompted recently by a quote shared by a fellow theology nerd, Keanu Heydari.

Now, I should clarify that Keanu is a real academic theologian while I am just an enthusiast, but he pointed us toward Barth’s visceral reaction to Billy Graham that really struck me.

First of all, Barth and Graham met through Barth’s Chicago-based son Markus. In fact, they met twice.

After Barth heard Graham preach at St. Jakob Stadium, Basel, Switzerland, in 1960, he did not hold back. He said, "I was quite horrified. He acted like a madman and what he presented was certainly not the Gospel. It was the Gospel at gun-point. He preached the law, not a message to make one happy" (Busch, Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts, 1976).

When I look at this through Barth’s eyes, I see a fascinating clash between two very different ways of sharing the faith. Even though Barth was a giant of the academic theology, he was also a man of deep convictions who had famously stood up to the Nazis.

When he first met Graham in Switzerland, he actually found himself liking the man personally. He called Graham a "jolly good fellow" and was impressed that the famous evangelist was such a good listener (Barth, Letters 1961–1968, 1981).

However, that personal warmth did not change the fact that Barth was deeply troubled by the way Graham preached. He sat in that stadium in Basel under an umbrella during a rainstorm and left feeling that the entire approach was fundamentally flawed.

To understand my perspective on this, you have to understand that Barth believed the Gospel should be a message of pure joy and grace. For a Reformed thinker like Barth, the idea of using fear or the threat of hell to push someone into a religious decision felt like a form of spiritual coercion.

He told Graham that he hated the constant use of the word "must," like when Graham insisted that people "must" be born again (Graham, Just As I Am, 1997). Barth felt that this language turned the Good News into a high-pressure sales pitch. He believed that the proclamation of Christ should be an invitation to freedom, not a demand backed by a threat.

In their private talks, Graham defended himself by pointing to the words of Jesus in the Gospel of John, but Barth was not convinced. He felt that Graham’s style was like "pistol-shooting" from the pulpit (Busch, 1976).

As a theology nerd, I find this tension so compelling because it gets to the heart of what the Gospel really is. Is it a joyful invitation or a frantic ultimatum?

Barth respected Graham as a person, but he stayed convinced that the crusade model oversimplified the faith and relied too much on human pressure rather than the quiet work of God.

It is a classic example of how two people can be friendly while remaining worlds apart on the most important questions of how we talk about God.