Technically, there is no required ‘Order of Worship’ in the Presbyterian tradition

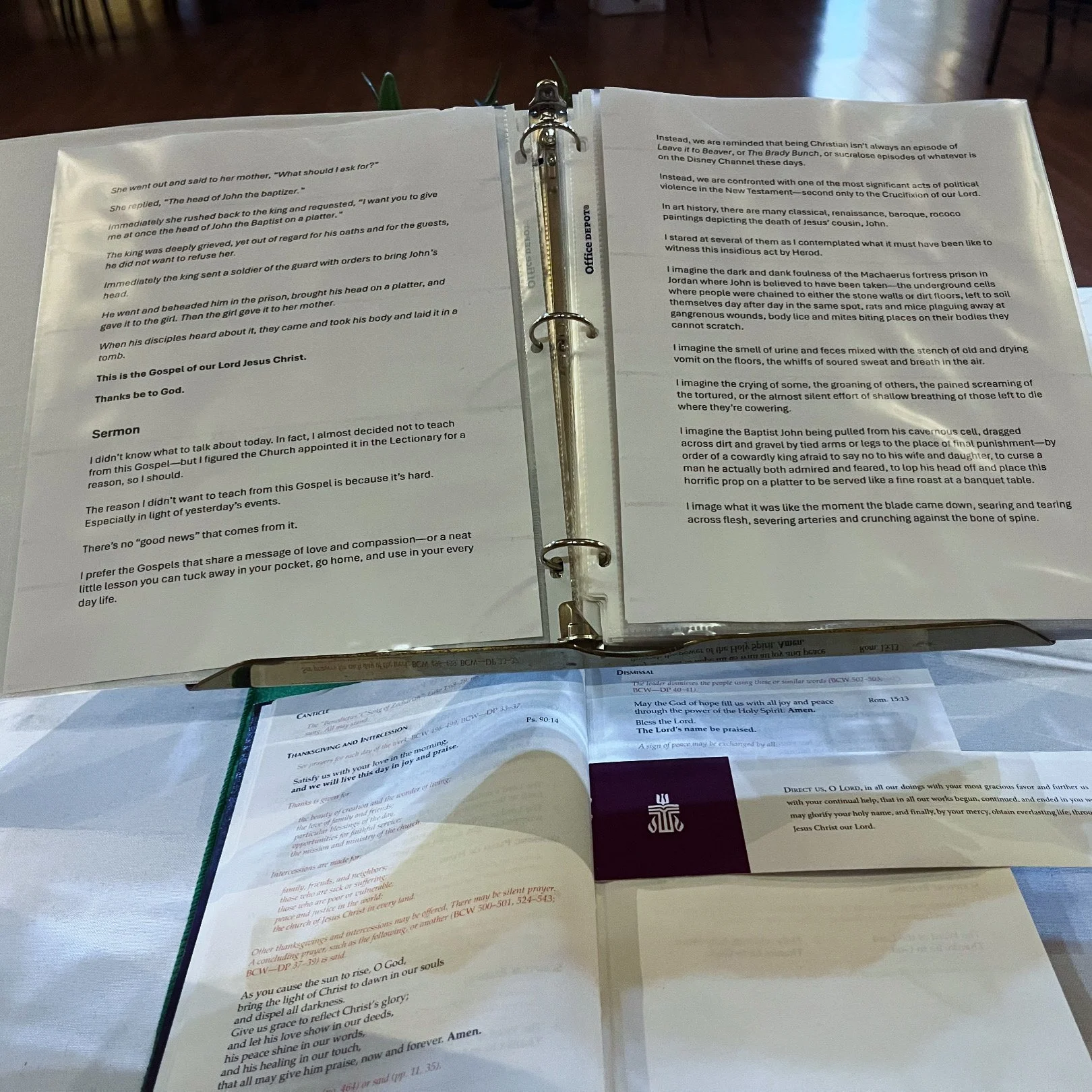

Photo: Gerald Farinas.

The idea of a rigid Sunday schedule is so deep in our bones that most people assume the order of worship is a set of rules. We expect the opening prayer, the hymns, and the sermon to arrive in their usual spots. However, if you look at the technical side of the Presbyterian tradition, there is a surprising amount of room to move.

There are actually no required parts of worship that must happen every single Sunday. While the PCUSA provides a guide for worship, it is meant to be a resource rather than a list of commands. This lack of a "must-do" list is not about being messy. It is a hard-won stance based on a long history of people refusing to be told exactly how to talk to God.

The Presbyterian tradition has always felt a bit uneasy about having a formal Book of Worship. In other traditions, people find comfort in a prayer book that stays the same everywhere. But for many early Presbyterians, these books were viewed with a bit of suspicion. They worried that reading the same printed prayers every week would make worship feel like a script instead of a conversation led by the Holy Spirit.

For many of these early believers, the only book you truly needed for a service was the Bible. Anything else felt like a human invention that might get in the way of a direct connection with God. This desire for freedom was a fierce commitment to the idea that worship should be shaped by Scripture, not by a committee.

This resistance reached a famous and violent peak in 17th-century Scotland. When King Charles I tried to force a version of the Book of Common Prayer on Scottish Presbyterians in 1637, he did not just get a few complaints. He started a riot.

The story goes that a woman named Jenny Geddes threw her stool at a minister the moment he started reading from the new Book of Common Prayer. That act of defiance helped spark a series of wars. The King believed he had the right to tell his subjects how to pray, but that turned out to be a very dangerous mistake.

The fight against this forced style of worship was a major reason the King eventually faced trial and was executed in 1649. King Charles literally lost his head because he tried to standardize the way people approached God.

Because of this history, the Presbyterian identity is built on a wariness of any document that claims to be a mandatory Book of Worship. Even today, the PCUSA makes it clear that the style and order of worship are the responsibility of the local Session and the minister. If a Session decided to change things up entirely, they would not be breaking any church laws.

In our tradition, a Session and minister together might decide that worship is just an hour of silence—not unlike a Quaker meeting. Or it could be two hours of just one sermon by the preacher. Or it could be thirty minutes of just music. The possibilities in the PCUSA are endless.

The freedom we have in worship today is a tribute to those who believed that no power on earth should have the final word on how we pray. We sit in our pews with a bulletin in hand, perhaps not realizing that the structure we follow is actually optional.

It is a funny irony that the tradition known for being "decent and in order" is also the one that refuses to force a specific order on its people. We are free to pray and sing because we want to, following a long line of rebels who preferred a headless king to a scripted heart.