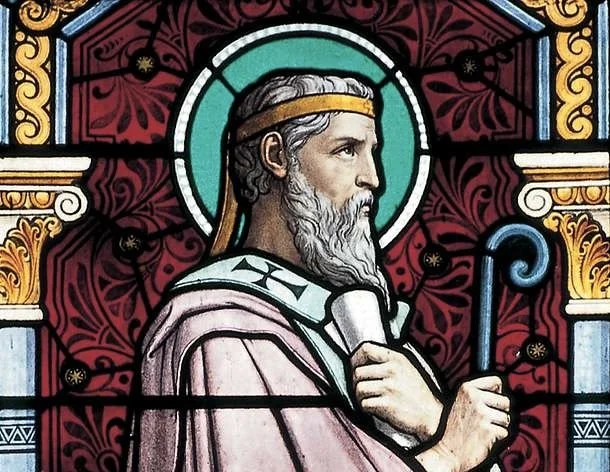

The early presbyter Irenaeus vs. those pesky Basilidian heresies

Photo: picryl.com. Public domain.

I have always had a bit of a soft spot for historical fiction and medieval horror. There is something about the atmosphere of the ancient world that makes for a perfect ghost story, and I recently stumbled across a group called the Basilidians while reading a novel called "In the Name of the Worm" by Mitchell Lüthi.

In the book, they are portrayed with a chilling, mysterious energy, but as I looked into them, I realized the real-life history of this group is just as fascinating as the fiction.

Back in the second century, the Basilidians were a branch of the Gnostic movement in Alexandria, Egypt. They followed a teacher named Basilides who had a very different take on the universe than what we find in the Church today.

To the Basilidians, the true God was totally unknowable and far removed from our world. They believed our reality was actually created by lower-tier angels. In their view, there were 365 levels of heaven, and they used the mystical name Abraxas to describe the power ruling over them.

The most controversial part of their belief system was how they viewed Jesus. Because they thought the physical world was "lesser" or even "bad," they couldn't wrap their heads around a divine being actually suffering or dying. They taught that Jesus performed a miracle on the way to the cross and swapped places with Simon of Cyrene.

In their version of events, Simon was the one who was executed while Jesus stood by laughing, eventually floating back up to the spiritual realm. To them, the point of faith wasn't about a sacrifice for sin; it was about learning secret passwords to get your soul through those 365 heavens after you die.

This did not sit well with early Church leaders like Irenaeus of Lyons.

[My estranged grandfather and my cousin were named after this Greek bishop.]

He spent a lot of time writing against the Basilidians because he believed that if the physical world was a mistake and Jesus did not actually suffer, then the entire faith was a sham.

Irenaeus argued that God made the world and called it good, and that Jesus’ pain on the cross was real and meaningful. He wanted a faith that was open to everyone, not a secret club for people with special knowledge.

In fact, the pressure from groups like the Basilidians is what forced the early Church to finally get organized. To stop people from making up their own versions of the story, the Church had to officially decide which books belonged in the New Testament.

They also created the first creeds, which were short statements of belief that everyone had to agree on. These creeds were designed specifically to block Gnostic ideas, which is why they include very physical details, like the fact that Jesus "suffered under Pontius Pilate" and was "crucified, died, and was buried."

It is wild to think about, but those ancient arguments actually paved the way for how I see the Church today, especially in a denomination like the PCUSA. Because the early Church rejected the Basilidian idea that the physical world is a prison, modern Presbyterians focus heavily on taking care of the Earth and fighting for social justice.

When the PCUSA talks about "creation care" or helping the marginalized, it’s because we believe that our bodies and our planet truly matter to God.

Instead of searching for secret codes to escape to a distant heaven, the legacy of this debate pushed us to look for God right here in the messiness of real life. We do not have hidden levels of faith; we have public confessions and a transparent way of doing things.

It’s funny how a horror novel about a second-century sect can lead right back to the reasons why we care so much about things like immigration and advocating for undocumented people, LGBTQ rights, and environmental stewardship in the present day.